The AMR Centre has today welcomed a new report from the BioIndustry Association (BIA), which highlights the ground breaking research being conducted by UK SMEs to tackle the health crisis posed by antibiotic drug resistance.

The report illustrates how advances across biology, technology, engineering and data science are converging to help create new solutions to the problem of our dwindling supply of effective antibiotics.

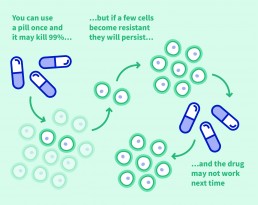

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has emerged as a priority in global public health in recent years. Bacteria naturally develop the ability to defeat the antibiotics we design to kill them. Unfortunately, drug development has failed to keep pace. Overuse of existing antibiotics in human and animal health has at the same time acerbated the problem, giving rise to superbugs that are difficult, and sometimes impossible, to treat. At present AMR claims around 700,000 lives a year but that figure is forecast to multiply. By 2050, if left unchecked, drug-resistant infections will kill 10 million people a year and cost the worldwide economy $100 trillion.

The BIA report showcases a number of new and highly innovative approaches being developed in UK labs. These include Destiny Pharma plc, a Sussex-based company which has anti-bacterial drug candidates that work differently to existing antibiotics. Studies suggest that they have a very low potential to elicit bacterial resistance, even in MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) one of the most dangerous multi-drug resistant pathogens. This is in part because they act ultra-rapidly, leaving little time for the superbugs to develop avoidance mechanisms.

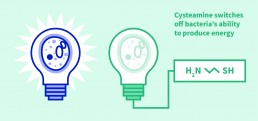

The Aberdeen-based Novabiotics, meanwhile is using some of the body’s own infection-fighting mechanisms as the basis for entirely novel antimicrobial medicines. The company’s scientists have taken inspiration from two kinds of rapid-response unit within our immune systems: aminothiols, a type of molecule produced during infection and inflammation, and anti-microbial peptides made by epithelial cells which form the barrier between our bodies and the outside world. Both these approaches kill bacteria or fungi very fast, preventing them from developing resistance.

Dr Peter Jackson, executive director of the AMR Centre, which is based at Alderley Park, Cheshire, commented: “It’s really pleasing to see this BIA report, which casts light on some of the cutting edge work in this field. For a variety of reasons big pharma has passed the baton to small and medium sized companies in terms of creating new drugs for bad bugs. The BIA report showcases many examples of novel and fresh thinking happening in the UK. Summit Therapeutics, for instance, is an example of precision medicine in action. The company is developing new antibiotics to treat infections caused by Clostridium difficile (CDI) bacteria. These infections are hard to treat and Summit’s lead candidate, ridinilazole, has been shown in clinical trials to attack pathogenic C. difficile strains in a highly selective fashion, sparing the many helpful gut bacteria that keep us healthy.”

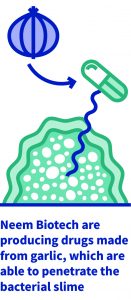

Others highlighted in the BIA report include Neem Biotech, which has drug candidates which disrupt biofilms – slimy layers of bacteria associated with some of the most stubborn infections, including those found in the respiratory tract and in wounds. Neem’s novel approach has its roots in garlic, long known for its healing properties. Academics at the Technical University of Denmark identified ajoene – one of several sulphur-based compound found in garlic – as responsible for disrupting the bacterial communication (known as quorum sensing) in biofilms. The BIA report describes how Neem’s team of microbiologists, chemists and biochemists have designed synthetic, well-characterised variants of ajoene which are more stable and easier to make than the original. Neem is developing these derivatives for chronic or hard-to-heal wounds and in chronic lung infections, such as those associated with cystic fibrosis.

Earlier this year the Swiss drugs giant Novartis became the latest big pharma company to announce an exit from AMR research, following Sanofi in 2017 and AstraZeneca in 2016. “The leading edge science in AMR is now in small and medium sized company – and that’s who we are here to help,” Dr Jackson added. “Given the seriousness and scale of the AMR problem we would still like to see more researchers in the field. There could be as few as 150 scientists in the UK currently focused on AMR. These scientists are doing valuable, important work but we need to see more incentives to help the business model make sense for big pharma. There are some good ideas out there which would support this – including the REVAMP proposals which may go before the US Congress next year.”

The AMR Centre has announced three programs to date. In a collaboration with EligoChem, a Kent-based drug discovery firm, it has supported the development of antimicrobial peptides to target the most critical drug-resistant organisms. It also has partnerships with Massachusetts clinical-stage drug development company, Microbiotix Inc, on program focused on T3SS inhibitors in a way that tackles infections by reducing virulence – a solution that does not encourage the bug to evolve resistance. The AMR Centre has a further program licensed from Stockholm-based Medivir to tackle the threat posed by an enzyme that makes bacteria resistant to widely used antibiotics such as penicillins.

https://www.bioindustry.org/policy/strategic-technologies/antimicrobial-resistance.html